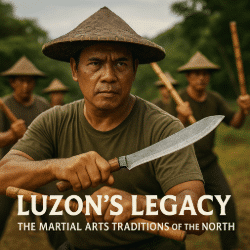

Luzon’s Legacy: The Martial Arts Traditions of Northern Philippines

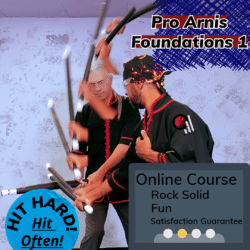

From pre-colonial warrior tribes to Modern Arnis and Kombatan, discover how the northern Philippines shaped the evolution of Filipino Martial Arts and preserved a living heritage of rhythm, resilience, and skill.