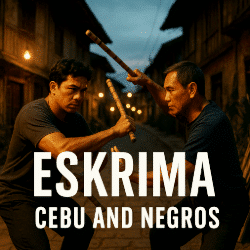

The Visayan Crucible: How Cebu and Negros Forged Eskrima’s Fast, Geometric Power

Cebu and Negros shaped the fast, geometric rhythm of Filipino martial arts. In the crowded villages and cane fields of the Visayas, Eskrima evolved into a close-quarter science of timing and efficiency—where every strike, angle, and pivot reflects island life itself.