Filipino Martial Arts: The Many Faces of a Living Warrior Tradition

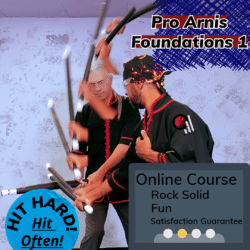

Discover the breadth of Filipino martial arts—from regional styles and weapon systems to modern training culture—culminating in the rise of Arnis as the national sport. A clear, practical overview for newcomers and practitioners alike.